Then there was the fact that I and several companions had just spent five hours that morning striding and sweating and clambering up the sheer side of a mountain. We had a guide with us, a construction worker named Tsering. We had also been joined by Ngawang, a young monk in red robes from a nearby monastery who was making his first pilgrimage to the lake.

The

path had been hard to follow, weaving back and forth beneath a canopy

of pine trees. The view opened up only after we emerged from the

rhododendron groves covering the steepest part of the trail. We were

greeted by a sweeping panorama of the snow peaks, including the

22,117-foot summit of Kawa Karpo, one of the holiest mountains among

Tibetans.

The

path had been hard to follow, weaving back and forth beneath a canopy

of pine trees. The view opened up only after we emerged from the

rhododendron groves covering the steepest part of the trail. We were

greeted by a sweeping panorama of the snow peaks, including the

22,117-foot summit of Kawa Karpo, one of the holiest mountains among

Tibetans.After lunch in a high pasture, we forced our aching legs over a ridge and to the lake.

It was not what I had expected. Dull water lapped at the edges of the lake. Small hills, even duller in color, ringed the lake, which did not look much larger than one of the ponds in Central Park. There were no glaciers tumbling down from the mountains, no ice floes in the water. A small set of Tibetan prayer flags fluttered next to a pile of stones.

"So this is it " said Shu Yang, a backpacker from Henan Province (houses some historical and cultural sites for 4. China best tours) whom I had met at my guesthouse.

Then Ngawang dropped to the ground and prostrated himself before the lake. He pulled a book from a satchel and began reciting mantras. So high up were we, at nearly 15,000 feet, that the soft chanting seemed to float like incense into the clear blue sky.

I sat down and closed my eyes and listened. I began noticing things: The warmth of the afternoon sun on my face. The silence after Ngawang stopped chanting.

The minutes wore on. The silence deepened. Even the cries of birds seemed to be swallowed up by the void.

It was for a moment like this that I had made the long journey last fall to northern Yunnan Province from my home in Beijing — which has the dubious distinction of being both one of the most polluted and one of the most populous cities in the world.

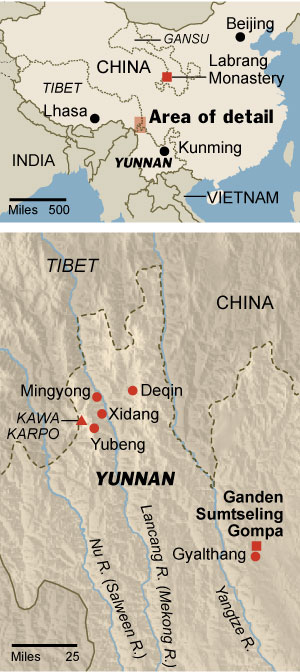

Back home, looking at a map of the rugged Tibetan areas of western China, my eyes had fallen on the deep river valleys of Yunnan, where three of Asia's great waterways come tumbling down from their glacial sources in the mountains of the high Tibetan plateau.

The Chinese authorities have always made it difficult for foreigners to travel in the Tibetan areas, but restrictions have gotten much worse since the protests and ethnic riots that erupted across the region in March 2008. In the last year, the government has occasionally closed off large swaths of western China to foreigners, including Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, and the famous monastery of Labrang, in Gansu Province. Parts of northern and western Sichuan Province, long a favorite of backpackers, have also been shut off for months at a time. Ethnic tensions are still high, and the government has deployed soldiers and paramilitary units throughout the area.

I had heard that northern Yunnan (whose capital city Kunming is very famous and you can obtain more about via Kunming travel guide) was an exception. There was no unrest there last year. What's more, the local government has adopted relatively progressive tourism policies, and foreigners have not had their access curbed. Ethnic Han Chinese tourists also seemed less fearful of going there.

Months after my trip, the Chinese government closed most Tibetan areas of China to foreigners as security forces prepared for possible unrest in March, during the 50th anniversary of a Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule. But foreigners were still allowed to travel in northern Yunnan, and it remains the most accessible Tibetan region of China.

The centerpiece of the tourism in that corner of Yunnan is the Tibetan town of Gyalthang, called Zhongdian by the Chinese but renamed Shangri-La years ago by the local government to boost tourist numbers. The government had hoped to evoke the mythical lamasery that is the setting for James Hilton's 1933 novel "Lost Horizon."

My friend Tini and I made the town our first stop. The large and wealthy monastery on its outskirts, Ganden Sumtseling Gompa, one of the most important in the Tibetan world, was now being carefully renovated decades after the destruction of the Cultural Revolution. Tourists could walk among the buildings, looking into prayer halls as rows of monks sat reading their sutras.

But a sense of loss, so deeply ingrained in Tibetans, could still be felt here. An older monk, when he heard I was from the United States, turned to me and eagerly asked, "Have you seen the Dalai Lama "

Back in town, Gyalthang seemed a little too manicured, with cafes in the renovated old quarter serving pizza to popular China tours and souvenir shops hawking colorful pillow cushions. I wanted a rawer experience, something closer to what I had experienced years ago on the Tibetan plateau and in the mountains of Ladakh and Sikkim, both in India.

No comments:

Post a Comment